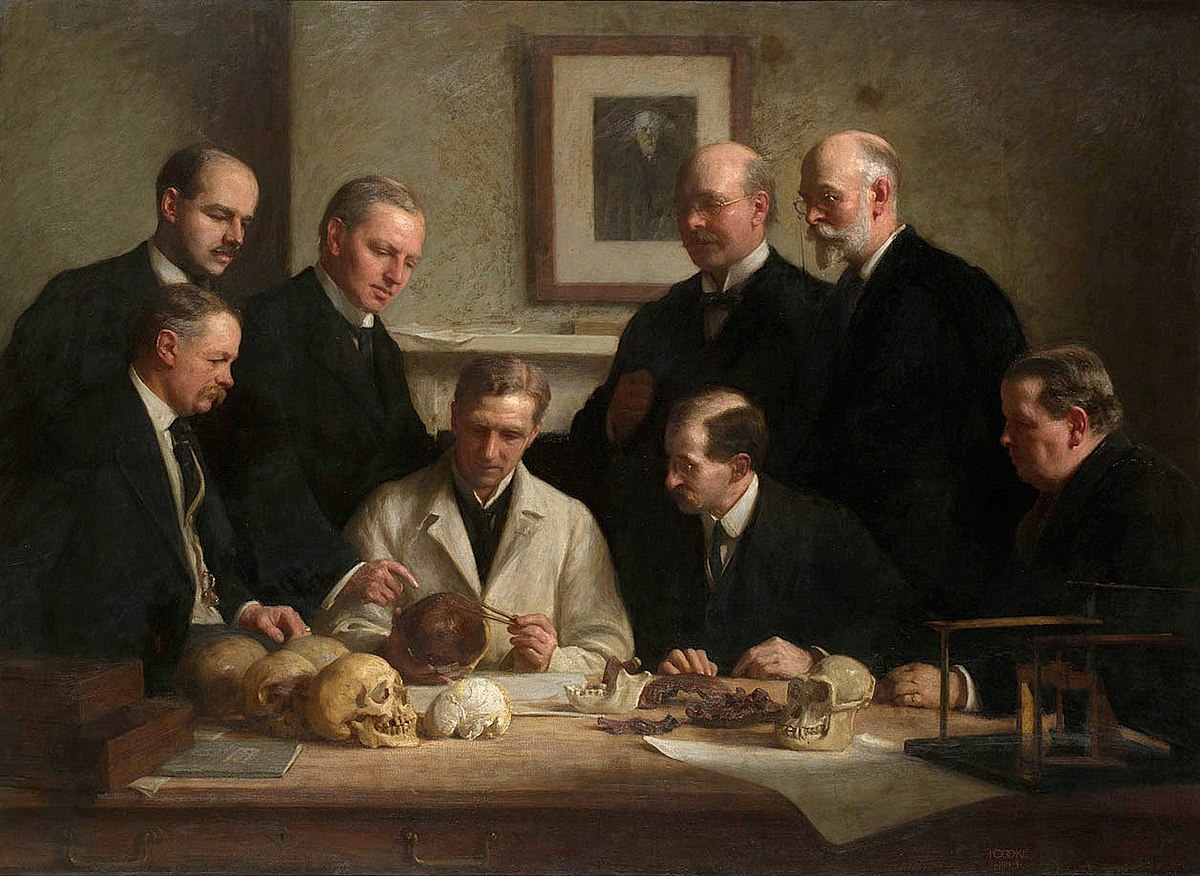

ON THIS DAY: 18 December 1912 – Amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson presented members of the Geological Society in London with a reconstructed skull, fragments of which had been discovered, he claimed, in a gravel pit south of Ashdown Forest in East Sussex. Dawson was backed by respected palaeontologist Arthur Smith Woodward from the British Museum, and the two men claimed that the skull represented an evolutionary missing link between apes and humans. The specimen combined a modern-looking cranium with a primitive jawbone, aligning with contemporary expectations about evolutionary progression. This skull, that of ‘Piltdown Man’, would later be revealed as one of the most famous scientific hoaxes in history.

Skepticism existed from the start, with some scientists questioning the incongruity between the skull and jaw features. However, the truth about Piltdown Man only emerged decades later. In 1953, new scientific techniques, including fluorine dating, revealed that the Piltdown fossils were not as ancient as claimed. The skull fragments were found to be only a few thousand years old. Detailed analyses showed that the jawbone belonged to an orangutang, with teeth deliberately filed down to appear more human.

The Piltdown Man hoax misled scientists for over 40 years and delayed the acceptance of other genuine fossils that did not fit the Piltdown narrative, such as the discoveries in Africa by Raymond Dart (Australopithecus africanus). While the identity of the perpetrator remains uncertain, Charles Dawson is the prime suspect. Others, including Smith Woodward and even the author Arthur Conan Doyle (a local resident and friend of Dawson), have been suggested as accomplices or unwitting participants.

Dawson had also claimed other archaeological and paleontological discoveries that were later found to be fraudulent. These included a ‘petrified toad’ inside a flint nodule and fake evidence of Roman occupation at Pevensey Castle in Sussex. Miles Russell of Bournemouth University concluded in 2003 that 38 of Dawson’s specimens were fakes.

Dawson did not live to see the hoax exposed. He died on August 10, 1916, at the age of 52, from septicaemia, or blood poisoning, likely caused by an infection. If Ashdown Forest cannot claim to be the preserve of the proverbial Missing Link, it did provide another, more enduring cultural hero. Four years after Dawson’s death, A.A. Milne’s son Christopher Robin was born, and Milne would soon begin writing his Winnie-the-Pooh stories, set in the Hundred Acre Wood—which was based on Ashdown Forest.