ON THIS DAY: 2 July 1839 – a courageous act of resistance took place aboard the Spanish slave ship La Amistad (whose name means, ironically, ‘friendship’). Fifty-three Africans who had been abducted from their homeland and sold into slavery in Cuba rose up against their captors in a bold bid for freedom.

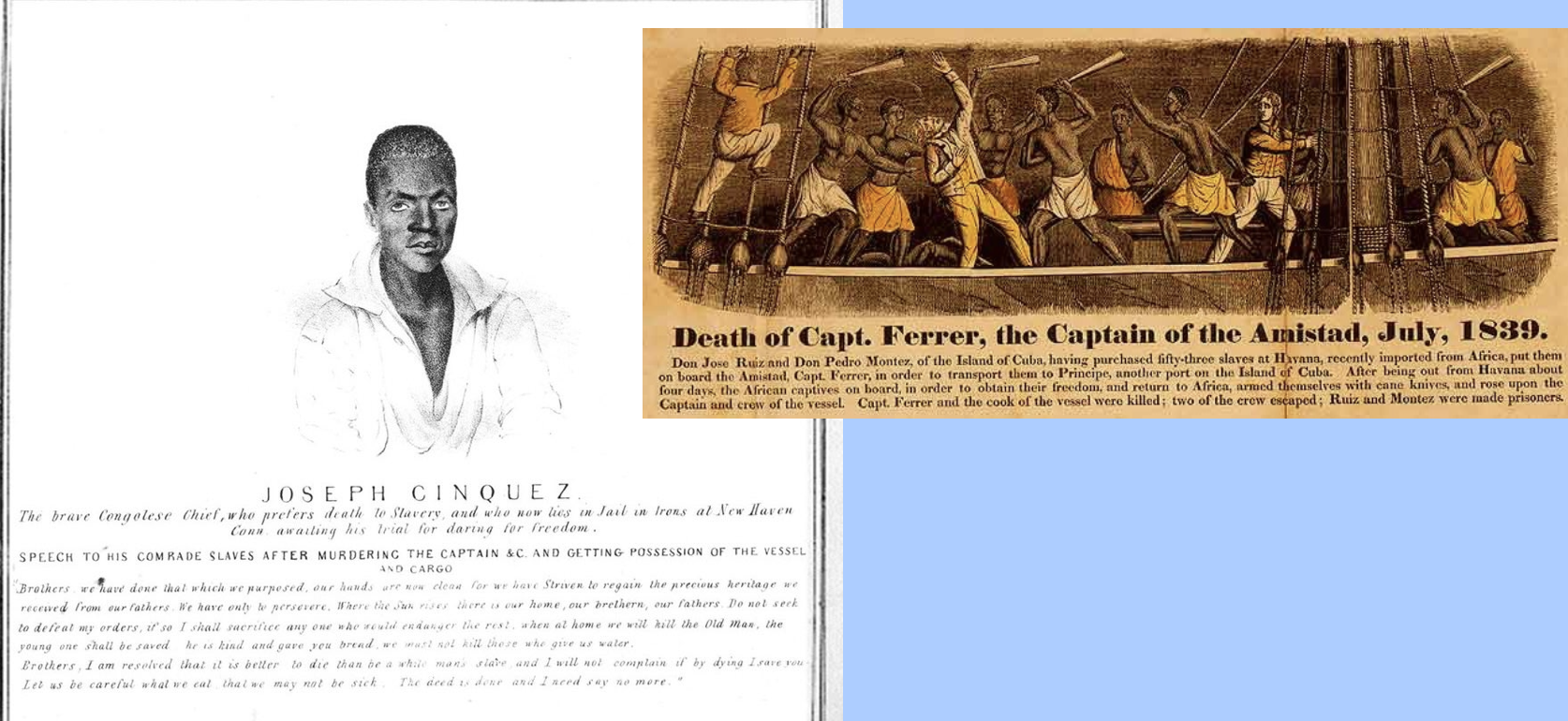

The captives had been purchased by two Spanish plantation owners, Pedro Montes and Jose Ruiz, who were transporting them from Havana to Puerto Príncipe (now known as Camagüey) in Cuba. But the journey took a different turn when one of the enslaved men, Joseph Cinqué, led a mutiny. The rebels killed the ship’s captain and cook, then demanded that Montes and Ruiz sail them back to Africa.

Instead, the Spaniards secretly steered the vessel northward. After two months at sea, La Amistad was intercepted by the U.S. Navy off the coast of Long Island, New York. The ship was towed to New London, Connecticut, and the African mutineers were jailed in New Haven—charged with murder. Montes and Ruiz were initially arrested for transporting Africans but were quickly released.

The Spanish embassy and the plantation owners demanded the return of the Africans and the ship to Cuba. But under maritime law, a ship or cargo rescued from impending loss ensures the rescuer, in this case Lt. Thomas R. Gedney, was entitled to claim salvage rights. In his claim, Gedney estimated the Africans, who spoke no English, were worth $25,000. But what followed was an unexpected turn of events: a federal trial in Hartford, Connecticut, in which abolitionists, led by Lewis Tappan, a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, brought national attention to the case. Legal support was secured from New York attorneys, and public sympathy grew for the Africans.

Still, political pressure mounted. President Martin Van Buren, facing re-election, ordered a U.S. Navy ship to be ready to deport the Africans back to Cuba immediately after the trial—assuming they would lose and hoping to avoid appeals.

But the judge ruled in favour of the captives. Though slavery was legal in Cuba, the international slave trade was not. The court declared that the Africans had been illegally kidnapped and were not property.

Unwilling to accept this decision, the U.S. government appealed to the Supreme Court. There, in a powerful moment in American history, former President John Quincy Adams took up their cause. In an eight-and-a-half-hour argument before the court, Adams defended the right of the Africans to resist ‘unlawful slavery.’

The Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision. The Africans were declared free.

With the help of private donations and missionary societies, the survivors—only 35 of the original 53—finally returned to Sierra Leone in January 1842. Many had died during their captivity or at sea. But their story became a landmark in the fight against slavery and a symbol of the enduring human spirit.