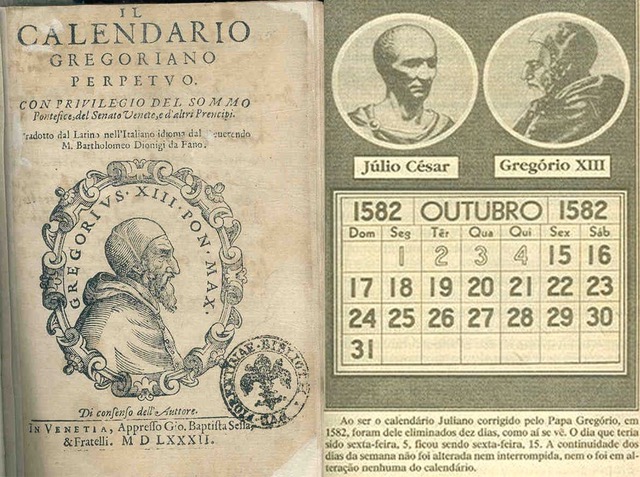

Britain adopted the Gregorian calendar, which had first been introduced 170 years earlier by Pope Gregory XIII in February 1582. As a result of this change, Britain lost 11 days from the calendar as the country fast-forwarded from early to mid-September in a matter of hours.

Prior to this, Britain had been using the Julian calendar, which was implemented by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE. However, the Julian calendar had an inherent error that caused a drift of one day every 128 years due to a miscalculation of the solar year by 11 minutes. This error caused significant problems, particularly affecting the timing of Easter, which was traditionally celebrated on 21 March. Over time, the date of Easter gradually moved further away from the spring equinox, leading to growing concern among scientists and religious authorities. British scientists and astronomers, including members of the Royal Society, advocated for a change to the more accurate Gregorian calendar to correct these inaccuracies and bring Britain in line with the rest of Europe.

The question arises as to why didn’t England adopt the Gregorian calendar in 1582 along with countries such as Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, and Poland-Lithuania. The answer lies in the religious and political landscape of the time. Those countries were under the influence of the Pope and had strong ties to the Catholic Church. England, however, had become predominantly Protestant following the Reformation and was wary of adopting anything perceived as “Papist” ideology. Another reason for England’s reluctance was the requirement to omit 10 days from the calendar to correct the error. This idea was met with scepticism and confusion, with many fearing they would lose days from their lives or that financial and legal arrangements would be adversely affected.

By the mid-eighteenth century, most of Europe had already adopted the Gregorian calendar, and Britain found itself increasingly out of sync with the rest of the continent. This discrepancy led to complications in international trade, diplomacy, and communication. Aligning with the European calendar became crucial for economic and political reasons. The British business community, especially as the British Empire expanded its trade networks across Europe and beyond, began to pressure the government for change. The differing calendars caused confusion in contracts, deadlines, and financial transactions, further highlighting the need for synchronization with the rest of Europe.

As a result, an Act of Parliament decreed that Wednesday, 2 September 1752, would be immediately followed by Thursday, 14 September, skipping 11 days. This change caused considerable anxiety, although there were some who found humour in the situation. For example, William Willett of Endon in Staffordshire famously wagered that he could dance around his village for 12 days and 12 nights. Beginning on the evening of 2 September 1752, he allegedly danced all night and finished the following morning on 14 September, thus claiming his winnings.

The last country to officially adopt the Gregorian calendar was Turkey, which made the change in 1927.