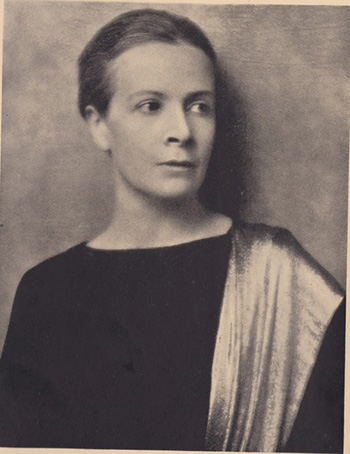

Constance “Stan” Harding is one of the twentieth century’s most curious, eccentric, endearing, often infuriating, and—sadly—long forgotten figures. In a life full of incident, the crucial moment came on 25 June 1920, when, working in Moscow as a British correspondent for the New York World, she was arrested as a spy, sentenced to death, and incarcerated in Lubyanka prison. Stan always maintained that she was innocent—something the Bolsheviks duly accepted—and that she had been falsely denounced by Mrs Marguerite Harrison, an American secret agent who was posing as a journalist while working for the Bolsheviks.

Stan was not one to accept her sorry fate. Following her release from prison in November 1920, she received £3,000 compensation from the Bolsheviks. Then, with the support of 200 hundred cross-party MPs in the British Parliament, along with such political luminaries as Lord Curzon and Bertrand Russell, she attempted to sue the government of the United States for employing the agent, Harrison, who falsely denounced her—an action that led to headlines around the world in 1923 (‘Women Writer says Yank Rival had her Jailed’, Chicago Tribune, 17 February, 1923). However, despite her notoriety, Stan and her remarkable story have largely disappeared from history, while that of Harrison, her ‘Yank rival’, has not. Stan appears in the pages of history, if at all, only as, quite literally, a footnote to Harrison’s story.

Stan Harding’s life is certainly not an open book. I only stumbled on her name when, while researching another topic, I came across a newspaper article printed in 1924 that recalled her quixotic attempt to sue the United States. I was astonished by this bravado. Who in her right mind would attempt to sue the American government? And why? So I went backwards from this point and slowly pieced together the story of this intrepid and sometimes foolhardy woman with a man’s name who seemed to mesmerise—and ultimately to frustrate and antagonise—virtually everyone she met.

Stan’s rather messy life was extremely difficult to unravel. It took me over ten years of research in Canada, the United States, Italy and all over the United Kingdom to piece together Stan’s rather chaotic life. I got U.S. government documents the National Archives declassified, and I had a ‘eureka’ moment in a back street in Florence, Italy, when I discovered where she had once lived a bohemian existence in an expatriate community. And there is still so much I do not know. Only a few newspaper articles with her by-line exist as she often supplied information to other journalists who used their own by-lines. Her memoir, The Underworld of State (1925), published in England, focuses on her incarceration in Russia and legal fight with Marguerite Harrison. Interesting as it is, it doesn’t shed much light on her early life and her years in the ‘paradise of exiles’ that was Florence. Her book was controversial enough to be suppressed by government officials in the United States. After the proofs were sent to him in October 1925, Colonel James Reeves, the head of Military Intelligence, claimed: ‘It is believed that it would be most undesirable to have this book published in the United States as it would only add fuel to an old controversy’.

Following Marguerite Harrison’s trail was easier. She was a socialite born in Catonsville, Baltimore, the daughter of a shipping magnet. Highly educated, multilingual and well-travelled, she is now known primarily as a travel writer. Her articles in the Baltimore Sun are fascinating, covering diverse topics ranging from New York theatre critiques to life in Berlin during the Armistice. She published several memoirs, which I highly recommend reading. To get further insight into Marguerite’s life I also recommend Women of the Four Winds by Elizabeth Fagg Olds, along with Catherine M. Griggs’s unpublished doctoral dissertation, ‘Beyond Boundaries: The Adventurous Life of Marguerite Harrison’. The National Archives in Maryland also have plenty of documents from Marguerite’s spying days. One document that I got declassified proves that she was a traitor who betrayed American agents to the Bolsheviks—something that surely removes some of her lustre and lends credence to Stan’s claims.

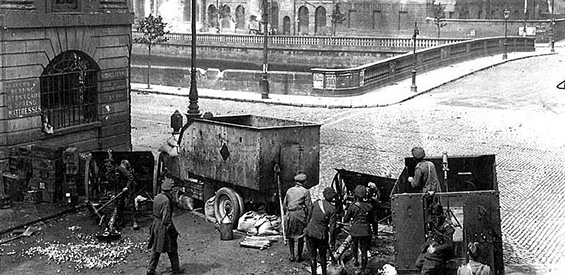

Both Marguerite and Stan led incredibly exciting lives, travelling to dangerous countries and plunging themselves into war zones, from insurrectionary Berlin during the Armistice to Moscow after the Bolshevik Revolution. And that is why, more than a century after Stan’s imprisonment in Lubyanka, I am writing a blog about her life. Marguerite is still being written about, quite understandably, but her story cannot be understood without taking the redoubtable Mrs Stan Harding into account. Stan does not deserve to be forgotten, nor should she be no more than a footnote in Marguerite’s life story. The jury is still out on which one of the women is telling the truth. But let us at least give them both the chance to tell their stories.

The Lady is a Spy: The Tangled Lives of Stan Harding & Marguerite Harrison

Illustrated Talk – 50 minutes

In the 1920s the names of two remarkable women, Marguerite Harrison and Constance ‘Stan’ Harding, were never far from the front pages of newspapers around the world. They were journalists who covered the violent uprisings in Germany after WWI and then the rise of Bolshevik Russia. They were also spies—Marguerite for the Americans, and Stan, according to Marguerite, for the British. A friendship ended in treachery and revenge after both were imprisoned in Moscow’s notorious Lubyanka Prison. This talk will introduce these two amazing women and tell the story of their tragically intertwined lives.

* There is a separate talk on Stan Harding focussing on her years in Florence.

* There is a separate talk on Marguerite Harrison’s career as a spy