ON THIS DAY: 13 August 1961 – In the early hours of August 13, 1961, something dramatic and deeply symbolic began to unfold in the heart of Europe. Under the cover of darkness, East German authorities swiftly closed the border between East and West Berlin. Barbed wire fences were rolled out with military precision, and armed soldiers sealed off streets and crossings. What began as a tangle of wire would soon harden into one of the most infamous structures of the 20th century: the Berlin Wall.

The urgency and speed of the operation caught many by surprise. But it was no improvised action. This was a calculated move by the East German government, backed firmly by the Soviet Union. The goal was clear: to stem the tide of East Germans fleeing to the West. From 1949 to 1961, approximately 2.7 million people – many of them young, educated, and skilled – had escaped through the relatively porous Berlin border. The losses were more than just human: they were economic, intellectual, and deeply political. For the East German regime, it was an escalating crisis and an international humiliation.

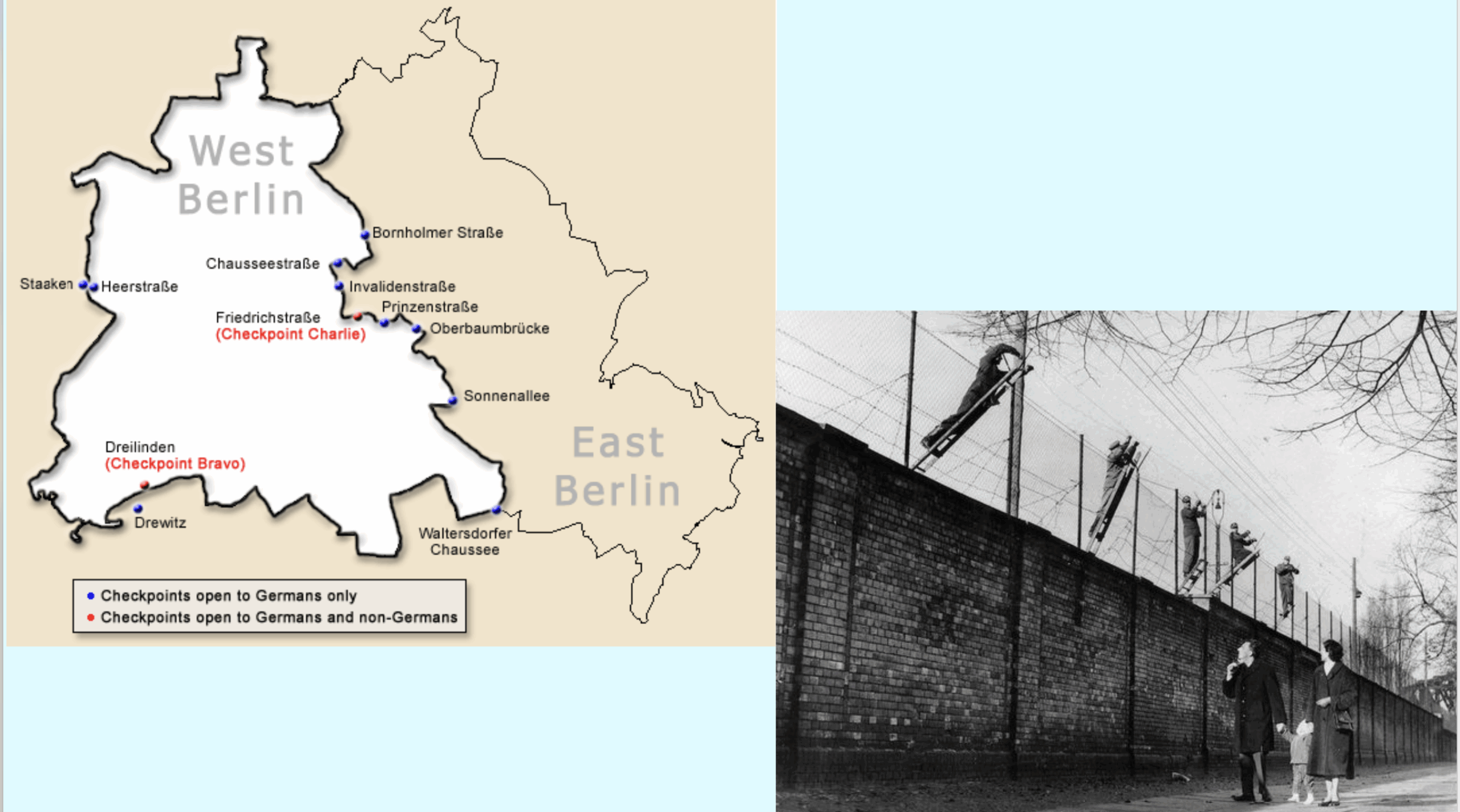

Post-World War II Germany had been carved into two ideologically opposed nations. West Germany, or the Federal Republic of Germany, was a capitalist democracy supported by the United States, Britain, and France. East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic, was a communist state under the control of the Soviet Union. Though Berlin lay entirely within East German territory, the city itself was divided. West Berlin became an island of Western influence surrounded by the communist East.

Construction began almost immediately after the border was closed. Within hours, barbed wire had cut through neighbourhoods, severing neighbours and families. In the days that followed, the wire gave way to concrete. By the end of August, the first version of the Berlin Wall was complete – a stark, grey division across a city once united. Over time, it evolved into a heavily fortified barrier, equipped with guard towers, floodlights, minefields, and the dreaded ‘death strip’: a no-man’s-land where countless lives were lost in desperate escape attempts.

But no wall lasts forever. By the late 1980s, cracks had begun to show – not in the concrete, but in the authority behind it. East Germans, inspired by reform movements across Eastern Europe and the liberalising policies of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev – glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) – began to demand change. Protests erupted across the country, and pressure mounted.

Then, on the evening of November 9, 1989, came the moment that would change history. In a muddled press conference, East German spokesman Günter Schabowski mistakenly announced that travel restrictions were being lifted ‘effective immediately’. The news spread like wildfire. That night, thousands gathered at the wall, demanding passage. Border guards, overwhelmed and uncertain, opened the gates. And just like that, the wall was no longer a barrier but a backdrop to joy and unity.

People climbed, chipped away at the concrete, and crossed freely. After 28 years, the Berlin Wall fell, not with a war, but with a whisper, a mistake, and the will of a people who had waited too long to be free.