ON THIS DAY: 25 June 1876 – Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer met his end at the Battle of the Little Bighorn—an event that would become famously known as Custer’s Last Stand. He was just 36 years old.

The battle, a key conflict in the Great Sioux War of 1876, took place near the Little Bighorn River in eastern Montana Territory. It pitted the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry Regiment, led by Custer, against a formidable coalition of Native American warriors—primarily Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho—under the leadership of Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Gall.

Tensions had escalated after gold was discovered in the Black Hills, a region sacred to the Lakota. In response, the U.S. government intensified pressure on Native tribes to relocate to reservations. Many who had already resettled abandoned the reservations to join the growing resistance against U.S. expansion.

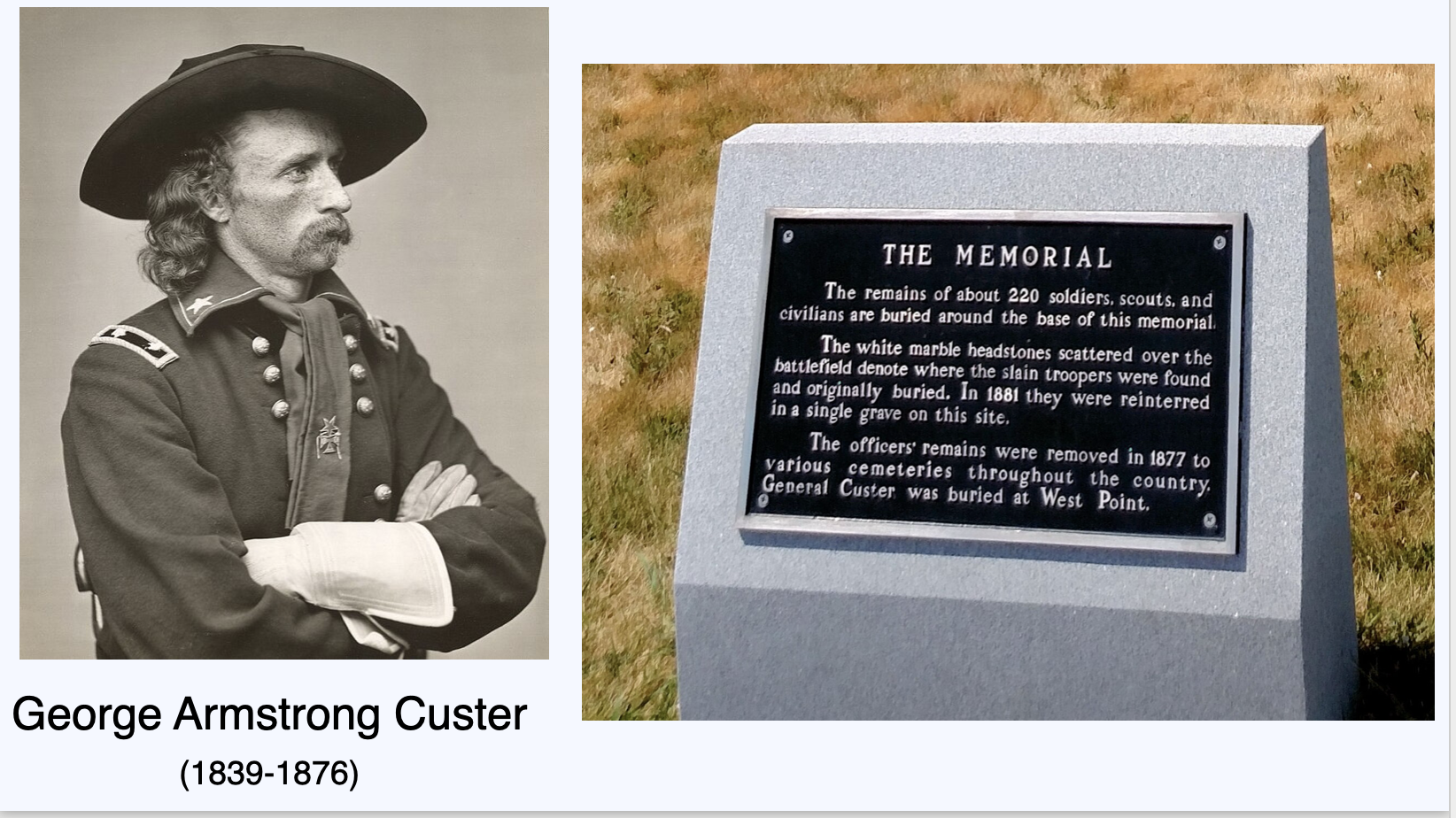

Distinguishing himself in the Battle of Gettysburg (1863), the Battle of Yellow Tavern (1864), and the Third Battle of Winchester (1864)—all before the age of 25—George Armstrong Custer earned the nickname ‘The Boy General.’ But it wasn’t just his daring on the battlefield that drew attention. Custer was equally known for his flamboyant military uniforms, his flowing shoulder-length blond hair, his distinctive moustache, and his piercing blue eyes. He cut a striking figure—equal parts soldier and showman—leaving a vivid impression on all who encountered him.

Custer’s regiment formed part of a larger, three-pronged military campaign designed to subdue the resisting tribes and force them back onto reservations. When Custer encountered a large Native village near the Little Bighorn River, he vastly underestimated the strength of the opposition—believed to be over 2,000 warriors. Opting for a surprise attack, Custer made the critical error of dividing his force of roughly 600 men into three separate groups. He neither waited for reinforcements nor anticipated the scale of the Native resistance.

The result was devastating. Custer’s detachment of approximately 210 men was completely overwhelmed. His body was later discovered on a hilltop—now called Custer’s Hill—with multiple gunshot wounds to the chest and head. Unlike many of his men, his body had not been scalped or mutilated, suggesting he may have been recognised by the victors.

The U.S. response was swift and brutal. In subsequent campaigns, the American military eventually forced the remaining tribes to surrender.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn has come to symbolise both Native American resistance and the tragic cost of westward expansion. Custer’s legacy remains deeply polarising—seen by some as a brave martyr, and by others as a reckless and egotistical commander whose miscalculations led to a needless slaughter.

Originally buried on the battlefield, Custer’s remains were later reinterred with honours at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Today, the site is preserved as the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, attracting approximately 28,000 visitors annually who come to reflect on one of the most iconic—and controversial—chapters in American history.